By Maka Chkhaidze

Monday, July 28, 2014

Are more educated women in Georgia choosing not to have children?

By Maka Chkhaidze

Posted by

Unknown

at

6:54 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Demography, Education, Gender, Georgia, Women

Monday, July 21, 2014

Friends and Enemies in the South Caucasus

Posted by

Unknown

at

7:59 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Cooperation, Ethnic war, European Union, Friendship, South Caucasus

Friday, July 18, 2014

Expectations and the EU Association Agreement

Today's blog post is published in collaboration with civil.ge. One may also read the post on civil.ge here.

On June 27, 2014 Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine signed EU Association Agreements. In Georgia, the signing has been celebrated as a step towards Euro-Atlantic integration, and a number of events were held in Tbilisi to celebrate the signing. The Association Agreement (AA) itself is wide ranging with some portions pertaining to human rights and the main focus on economic cooperation between the EU and Georgia. While the agreement has been highly anticipated by certain groups within Georgian society, there has been controversy, particularly as the association agreement relates to the protection of minority rights. A recent article on Foreign Policy Magazine’s website, and an accompanying case study by the Legatum Institute, argue that skepticism towards the EU may pop up in Georgia, in part, due to the EU’s seeming lack of engagement with the country over time. However, this trend is not new as Adrian Brisku notes in his 2013 comparative history of Georgia and Albania, Bittersweet Europe. With this background in mind, this post looks at how Georgians perceived both the EU and the Association Agreement approximately one year before the signing of the agreement. The post will review knowledge of the Association Agreement in Georgia in 2013 by settlement type and ethnic composition, expectations for the agreement by age group, and trust in the EU over time.

According to the 2013 survey, Knowledge and Attitudes toward the EU in Georgia which was a part of the Eurasia Partnership Foundation European Integration program, 20% of Georgian citizens reported that they had heard of the EU Association Agreement. Awareness of the association agreement was highest in the capital with 30% of Georgians reporting they had heard about the association agreement. In urban and rural settlements 17% and 16% of Georgians respectively reported that they had heard about the Association Agreement.

As the graph below demonstrates, Armenian and Azerbaijani minorities in Samtskhe-Javakheti, Kvemo Kartli and Kakheti were much less likely to be aware of the Association Agreement compared to their fellow ethnic Georgian citizens. Low levels of awareness of the Association Agreement among ethnic minorities are likely due to low levels of knowledge of Georgian language in ethnic enclaves. These groups also have less access to media which is in the Georgian language. In addition, there is a lower level of internet usage reported by minorities in the aforementioned settlements (12% daily usage, 62% never using the internet), especially compared to ethnic Georgians in the capital (51% daily usage, 29% never using the internet). This is a likely barrier to access to information.

People who said they had heard about the Association Agreement were asked what they thought the agreement could bring to Georgia. Survey respondents were asked to select one answer from a list provided on a show card. Looking at the results of this question by age group shows an interesting trend. Half of young people (18 to 35) stated that the agreement would result in political closeness and tight economic integration with the EU - the stated purpose of the agreement. In contrast, those aged 35 to 55 were more likely to report EU membership for Georgia as a result of the agreement. This outcome is not ruled out by the agreement, and in some instances, the agreement has served as a stepping stone on the path to EU membership. However, it is not an explicit or likely near-term result of the signing. Notably, a number of countries which are highly unlikely to want or be considered for EU membership have signed Association Agreements, including Algeria and Chile among other countries.

The graph below shows trust in the EU over time in Georgia. In 2008 trust in the EU was at 64%, followed by a slight decrease in trust which remained stable from 2009 to 2012. Interestingly, in 2013, a decrease in the level of trust occurred with trust responses dropping 16 percentage points, distrust increasing by seven, and neither trust nor distrust increasing by eight percentage points. Thus, a more ambivalent attitude towards the EU appears to have emerged in 2012 and 2013.

Note: Respondents were asked “Please tell me how much do you trust or distrust the European Union?” In the graph above, ‘fully trust’ and ‘somewhat trust’ are combined to form “Trust” and ‘somewhat distrust’ and ‘fully distrust’ are combined into “Distrust”.

This post has shown that awareness of the Association Agreement in Georgia is lower among ethnic minorities than ethnic Georgians in Georgia, likely due to lack of access to Georgian-language media and knowledge of Georgian. It has further discussed expectations among different age groups for the agreement, showing that young adults in Georgia expect closer ties from the agreement, while 36-55 year olds are more likely to believe that the agreement will lead to EU membership. Finally, the post looked at trust in the European Union over time. While distrust has not increased, ambivalence does seem to be spreading among Georgians, particularly in 2013. To further explore issues related to international organizations and the EU in Georgia, and the South Caucasus more generally, we recommend exploring our datasets here or using our Online Data Analysis Tool here. Readers may also be interested in the blog, Can’t get no satisfaction. Who doesn’t want to join the EU? published in March 2014 on the CRRC blog.

Posted by

Dustin Gilbreath

at

2:02 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: ethnic minorities, European Union, Knowledge, Media, Trust

Monday, July 14, 2014

When is a war not a war?

When is a war not a war? While it may seem commonsensical that a country cannot simultaneously be at war and at peace, the prevalence of several ‘frozen conflicts’ in the post-Soviet space defies simple categorization. If we take the conflict between Georgia and Abkhazia or South Ossetia as an example, a quick internet search shows that there was a five-day war in 2008 that ended on the 12th of August with a preliminary ceasefire agreement. Nevertheless, according to CRRC’s most recent Caucasus Barometer (CB) survey in 2013, almost no Georgians think that the conflict in Abkhazia had been resolved. Alternatively, Armenians and Azerbaijanis tend to support the idea that resolution has been achieved in Abkhazia (with 27% and 13%, respectively selecting this option), while differing significantly on their opinions about the status of their own territorial dispute over Nagorno-Karabakh (with 38% of the Azerbaijani population placing this as their highest national concern, compared to only 3% of Armenians). This raises the possibility that conflict is as much about perceptions as it is about actual military confrontation, and that national, regional and international conflict narratives can diverge significantly.

Thus, the conclusion that Georgia’s own territorial disputes can be condensed into five days underestimates the enduring negative impact of the status quo on all sides. Trade and travel are prohibited for inhabitants of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. De-isolation tops Abkhaz policy priorities, while the government in Tbilisi faces the ongoing challenge of settling and providing for internally displaced persons (IDPs).

In addition to the Georgia-Abkhazia and Georgia-South Ossetia conflicts, the conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia over the status of Nagorno-Karabakh is also called ‘frozen’, although experts like Thomas de Waal have suggested that the term ‘simmering’ might be a more appropriate designation. CRRC data is also instructive in this regard. When asked about the top two issues facing their respective countries, 38% of Azerbaijanis named unresolved territorial disputes as the number one problem in Azerbaijan, while 3% of Armenians and 10% of Georgians said the same. The figures in Azerbaijan and Georgia strongly suggest that these issues are not ‘frozen’ (or resolved) in the minds of the local population, although economic concerns also dominate throughout the region.

This blog has shown that national perceptions of conflict can contradict both regional and international narratives. This suggests that our current measures of war and peace are missing an important dimension. The CB provides a starting point for exploring the subject of war narratives. You can find comments about past perceptions of conflict resolution for the Azerbaijani-Armenian case here and for the Georgian case here. You can also access a report on Russian public opinion towards the future of these disputes here. Annual survey data for the South Caucasus region is also available for analysis on the online CB platform.

Posted by

Emily Knowles

at

8:03 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Abkhazia, Attitudes, Conflict Resolution, Nagorno Karabakh, South Caucasus

Monday, July 07, 2014

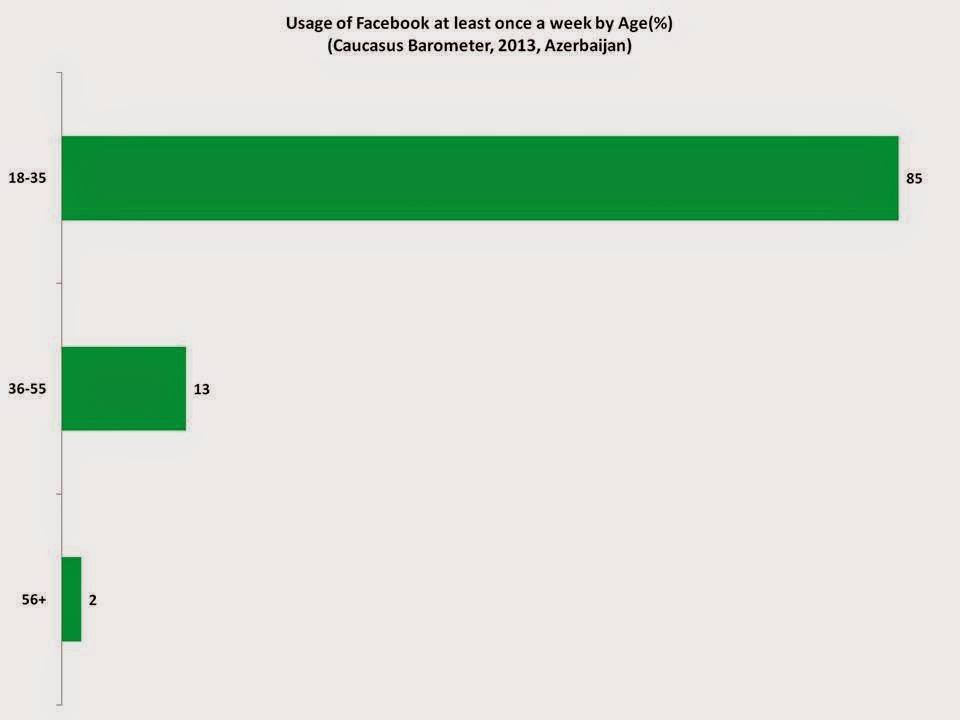

Facebook usage in Azerbaijan

On February 3rd, 2014, Facebook celebrated its 10th anniversary. According to the World Map of Social Networks December, 2013 statistics, Facebook is the world’s most popular social network with more than one billion users. It is followed by QZone with 552 million users, Vkontakte (190 million users), Odnoklassniki (45 million users), and Cloob (1 million users). However, it is important to note that social network usage is not distributed evenly geographically. In some countries different social networks have more usage than Facebook: for example, QZone in China, Vkontakte and Odnoklassniki in Russia, and Cloob in Iran. This blog post examines the usage of Facebook and its popularity among different age and gender groups in Azerbaijan.

In Azerbaijan, according to the annual Caucasus Barometer (CB) survey, 57% of the respondents reported using the Internet in 2013. Use of social networking sites was reported as the most popular activity on the Internet. Other activities, such as searching for information (49%), downloading/listening/watching music/videos (36%), and using Skype (33%) were also mentioned.

Facebook is the most popular social network in Azerbaijan, and it is used quite frequently.According to the CB, 16% of all respondents in Azerbaijan actively use Facebook. Moreover, 49% of Internet using respondents in Azerbaijan use Facebook at least once a week. Most Facebook users are males (65% according to Socialbakers statistics from 2014, 68% according to the CB), and the majority are young people aged 18-35 years old (72.8% according to the Socialbakers from 2014, and 85% according to the CB).

Among the respondents of the CB, almost 1/3rd of active Facebook users are posting news, personal observations or photos (30%). Other frequent Facebook activities mentioned by CB respondents in Azerbaijan included: commenting on other people’s posts and photos (26%), chatting (20%), and reading or viewing news-feeds (18%).

Besides connecting people as a tool for communicating with friends and family, Facebook has also made it easier to share opinions about information. Most CB respondents in Azerbaijan (88%) did not find it hard to express their opinion on Facebook. However, 5% of respondents expressed difficulty. Notably, posting opinions on FB is harder for women than men (10% of female respondents consider it hard to express their opinions on Facebook, while only 3% of male respondents express similar difficulty).

According to Statistics Brain Facebook data from 2014, the average number of friends per person on Facebook is 130. In Azerbaijan, 39% of CB respondents said they had 51-100 friends, whereas 37% of respondents had less than 50 friends on Facebook. Only 18% of respondents had more than 100 friends. The evidence suggests that for most Facebook users in Azerbaijan, the social network is a platform for connecting with their relatives and close friends; preferring a more selective form of communication, rather than communicating their thoughts, ideas and personal information to a larger audience.

To get more information about the Caucasus Barometer data and others activities by CRRC, we recommend following us on our Facebook page here. To learn more about Facebook usage in Azerbaijan and other South Caucasus republics, we recommend accessing Caucasus Barometer data here with our Online Data Analysis (ODA) tool.

By Aynur Ramazanova

Posted by

Dustin Gilbreath

at

7:55 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Age, Azerbaijan, Civic Engagement, Gender, Internet